In the more than 100 years since Edmond Locard established the first police crime lab, law enforcement personnel have been meticulously securing and investigating crime scenes, searching for clues that will help them solve cases.

The logic behind crime scene investigation (CSI) stems from Locard’s “exchange principle.” The French criminologist and forensic science pioneer concluded that a perpetrator cannot leave a crime scene without introducing something to it or carrying something away from it.

Though CSI techniques and technologies have changed over time, one thing that hasn’t is the significance of properly securing and processing crime scenes. It’s why schools like Pitt Community College include courses on “Investigative Principles,” “Investigative Photography” and “Criminalistics” in their Criminal Justice Technology curricula.

Though CSI techniques and technologies have changed over time, one thing that hasn’t is the significance of properly securing and processing crime scenes. It’s why schools like Pitt Community College include courses on “Investigative Principles,” “Investigative Photography” and “Criminalistics” in their Criminal Justice Technology curricula.

“Crime scene investigation is not simply searching high and low to collect evidence,” PCC Criminal Justice Technology Instructor Mike Nicholson said. “There’s a proper way of doing it, and we make sure our students understand the importance of following time-tested procedures, to not only identify a suspect of a crime but to successfully prosecute that individual in a court of law.”

History has shown that when crime scenes are properly secured and examined, it leads to arrests and convictions of murderers, like Ted Bundy, Wayne Williams and Dennis Rader. It’s helped law enforcement identify Bruno Hauptmann as the man who kidnapped and killed Charles Lindbergh’s baby in 1932 and Gary Ridgway as The Green River Killer in 2001.

But when CSI is conducted improperly, as was the case in the Black Dahlia murder and, more recently, JonBenet Ramsey’s death, a crime may never be solved. And even if a suspect is eventually identified and charged, convincing a jury of that person’s guilt is considerably more difficult.

But when CSI is conducted improperly, as was the case in the Black Dahlia murder and, more recently, JonBenet Ramsey’s death, a crime may never be solved. And even if a suspect is eventually identified and charged, convincing a jury of that person’s guilt is considerably more difficult.

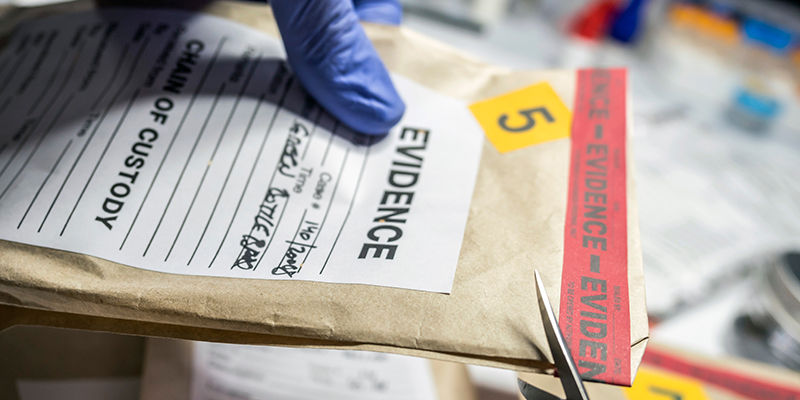

“When mistakes are made in the collection, handling and storage of crime scene evidence, it makes law enforcement’s job infinitely harder,” Nicholson said. “At the same time, it makes it much easier for defense attorneys to have cases dismissed or result in not guilty verdicts and hung juries.”

He went on to explain that there’s a good chance evidence collected through sloppy technique or taken from contaminated crime scenes will be thrown out in a court of law. In those instances, he said defense attorneys will argue that evidence that has been improperly handled or stored is not reliable and may convince a judge that it shouldn’t be presented to a jury.

“You really don’t get a second chance to investigate a crime scene, because once it has been released and the yellow tape barrier has been removed, the reliability of evidence discovered later on is greatly reduced,” Nicholson said. “When a crime has been committed, it is critical for law enforcement to cordon off the area where the incident occurred and search for evidence as thoroughly as possible the first time around.”

Nicholson says PCC instructors show their students what to look for at crime scenes and how to secure them, so that evidence discovered at the sites cannot be contested. They teach them the most up-to-date collection and storage techniques and technology, how to prepare reports, and how to discuss their investigative work in a courtroom.

“We often read and hear about DNA’s accuracy and how it doesn’t take much DNA left behind at a crime scene to help law enforcement identify a suspect, especially if that person’s DNA is on file in a national database,” Nicholson said. “But if a DNA sample is contaminated, it’s useless in a court of law, which is one of the reasons why following proper collection, handling and storage practices is so important.”

Another key area of PCC’s Criminal Justice Technology program focuses on crime scene photography. Students learn how to operate digital photography equipment, how photography applies to crime scene investigation, and the methods for retrieving and preparing digital images as evidence.

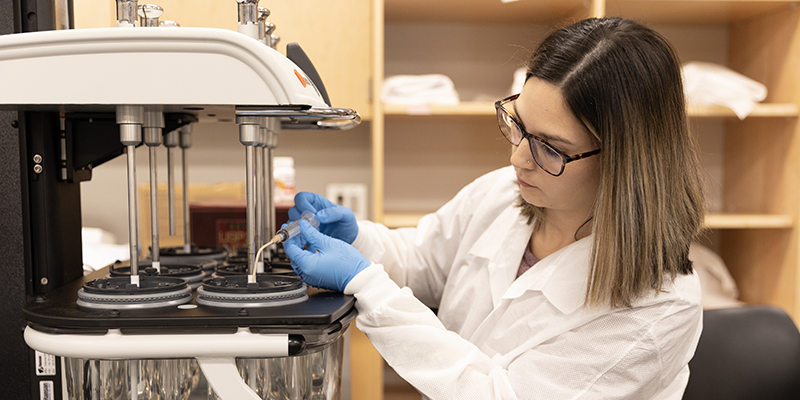

Through their criminalistics coursework, Pitt students study the functions of forensic labs and how they factor into successful criminal investigations and prosecutions. Instruction includes identifying and collecting relevant evidence from a simulated crime scene and requesting lab analysis of submitted evidence.

At the beginning of each semester, Nicholson says every student receives a crime scene investigation kit that includes materials needed to collect fingerprints, a camera, crime scene tape, tweezers, a tape measure, footprint casting plaster, several types of evidence collection bags/tubes, a magnifying glass and personal protection equipment. He said they’re also given basic traffic crash reconstruction templates to create traffic crash diagrams, forensic goggles and fluorescent powders, and, for evidence not visible to the naked eye, black lights.

“We typically set up crime scenes, investigate them and take them down during classes,” Nicholson says. “We want to be certain that when our students complete their associate degrees, they are familiar with the equipment used to conduct investigations and are proficient using them.”

For Nicholson, the bottom line when it comes to crime scene investigation is solving crimes. It’s why PCC’s Criminal Justice Technology program gives students hands-on training opportunities along with thorough instruction on the process.

“It’s not about wins and losses in a courtroom,” he said. “It’s about getting justice for victims of crime and their loved ones.”